By KAY MATTHEWS

The proposed Southwest Jemez Mountains Restoration Project (SJMRP) is off to a rocky start and we’re just through the scoping period. Several letters to the editor in the Santa Fe New Mexican referenced Santa Fe National Forest (SFNF) fuels specialist Bill Armstrong calling ponderosa pine trees “weeds” and that we need to “get rid of 95 percent of them.” Armstrong, who has been with the SFNF longer than any forester I can think of, has often put his foot in his mouth over the years, but he’s also credited with lobbying for desperately needed thinning in the Jemez since the 1990s.

Theoretically, considering what’s happened to the Jemez Mountains over the past few decades it’s hard to understand why anyone would oppose a rigorous management plan of thinning, prescribed burning, and watershed restoration, which is what the SJMRP proposes. In practice, of course, it was a prescribed burn at Bandelier National Monument that started the Cerro Grande fire. You can also question United States Forest Service (USFS) policies that helped create monolithic tinderboxes like the Jemez, and why the service is now dependent upon special funding to do the work that local loggers could have done to keep their businesses alive. Instead we have a long history of crown fires that have burned through this range and threatened Los Alamos National Laboratory: the 1954 Water Canyon fire of approximately 5,000 acres that forced the first evacuation of Los Alamos; the 1977, 15,000-acre La Mesa fire; the 1996, 16,000-acre Dome fire; the 2000 Cerro Grande fire, which burned 43,000 acres and forced another evacuation; and the 156,000-acre Las Conchas fire, then the largest fire to date that also forced evacuations at Los Alamos and Santa Clara Pueblo (the 2012 Whitewater-Baldy fire in the Gila broke that record).

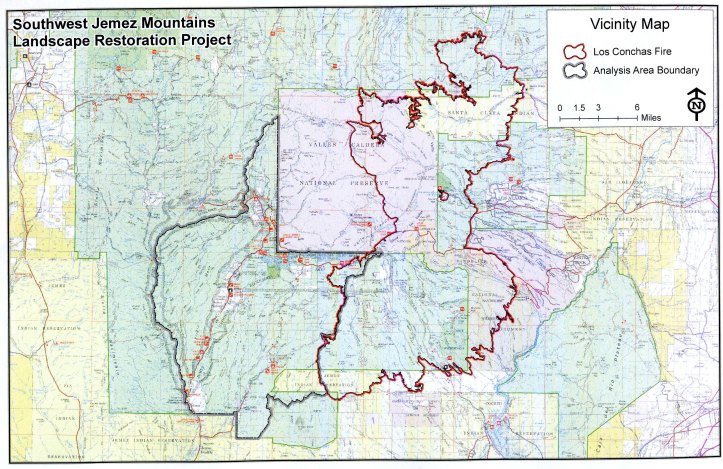

The SJMRP was among ten nationwide projects selected by the United States Department of Agriculture (the United States Forest Service is part of the USDA) in 2010 for funding under the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP), not to be confused with the Collaborative Forest Restoration Program that has funded numerous local forest related projects over the past 11 years in all the forests of New Mexico.

Thirty-five million dollars of the estimated $80 million cost of the SJMRP will be funded by CFLRP over the next 10 years; the rest will be underwritten by regularly appropriated USFS funds, other grants, and possible service contributions (more on this later). The project is being fast tracked: the scoping period for the project ends on August 13; a draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) is scheduled for April 2013, a Record of Decision for August of 2013.

The project proposes to thin trees on 90,000 acres and use prescribed fire on 76,000 acres within the Jemez Ranger District and the Valles Calera Preserve. Portions of Bandelier National Monument, Santa Clara, and Jemez Pueblos are also included. Most of the thinning is proposed for the ponderosa pine forests, but mixed conifer, piñon/juniper, and aspen are also slated for treatment. Site specific methods will be used: chainsaws, mechanized equipment, or whole-tree mastication. Wood removal techniques will also be site specific: firewood sales, commercial harvest, and prescribed burning. The ponderosa pine will be thinned to establish groups of trees between 4 and 20 trees to a stand (the mixed conifer thinning is similar to this prescription). Riparian areas throughout the project area will be treated by various methods: planting of native plants; streambank stabilization; repair of degraded trails and campsites; treatment of headcuts; and protections of meadow habitat. Wildlife habitat and archeological site protection and improvements are also included in the project.

At the public hearing at SFNF headquarters on August 2, Forest Service personnel devoted most of their presentation to prescribed burning and the methods of tree thinning and removal, always the most controversial components of a project like this. The fire management specialist carefully went over the procedures that have been developed since the Cerro Grande fire to prevent another conflagration of that magnitude. The Interagency Prescribed Fire Planning Document is their Bible, from which they run computer modeling based on temperature, humidity, wind speed and direction, and smoke dispersion.

Where there’s fire there’s smoke, of course. A planning section chief from the New Mexico Environment Department’s Air Quality Bureau was at the meeting to talk about the risks to public health and visibility that may result from prescribed burning. What is called “fine particulate matter” has the most impact on the public, particularly those with respiratory problems and young children. The smoke from the Wallow Fire, which burned last year in Arizona, 150 miles away from Albuquerque, exceeded health standards for seven days with a 200 fine particulate count in the city. The smoke from last year’s Las Conchas fire had a count of 1,000 in Albuquerque. The Forest Service air quality control specialist at the meeting stressed that managers strive for a prescribed burn that will send the smoke straight up into the air where it is then dispersed at a higher elevation.

Several of the New Mexican letters raised the specter of, oh my God, “commercial logging” as a method of tree thinning and removal. What the USFS actually has in mind acknowledges that there are almost no commercial loggers left in New Mexico, that there’s no market for small timber, and since CFLRP is footing most of the bill the Forest Service can hope for an “even trade”: through stewardship contracts the Forest Service will exchange goods for services. The bidding contractor can determine the value the wood they can use and trade that against what they would have charged to thin the smaller trees that they can’t use. According to the silviculturist at the meeting, the goal for the Forest Service is to pay “next to nothing.” Of the acres slated for thinning, about half have harvest potential. Other methods will include firewood sales, service contracts (thinning), and prescribed burning on very small diameter trees.

As the silviculturist so eloquently—with his tongue in cheek—put it, “We are getting behinder and behinder” in the race to thin and burn the hundreds of thousands of acres in the SFNF that need treatment. Today the Forest Service is mechanically treating 3,000 acres a year and burning 10,000 to 13,000 acres. According to the forester, ponderosa pine forest should burn every seven years or so; there are thousands of acres that haven’t burned in a hundred years.

Although the scoping period just ended, there will be opportunity for public comment when the DEIS is released, supposedly next April. It remains to be seen if the SFNF can compress the National Environmental Policy (NEPA) work that usually takes three years on a project of this magnitude into the projected one-year timeline. While some project areas are already NEPA ready (archeological, wildlife, and other resource clearances), many more must be analyzed and approved within this short time frame. La Jicarita will follow this project as it progresses through the NEPA requirements towards some actual work on the ground.

First we let the Forest Service clear cut the Jemez in the ’60’s through the ’90’s, removing the resilient white fir, douglas fir and spruce to create a ponderosa pine plantation emulating the pure ponderosa forests of northern Arizona because it’s the preferred timber species. Then we let them tell us that a ponderosa forest needs burning every few years for health. Now we’re told that the prescription for a forest ravaged by out-of-control burns needs more fire for its own good. The Jemez plan “says” that more trees will be thinned than burned but the maps on the SFNF website show that at least 90% of the area is due for burning, including many areas that were replanted (with ponderosa pine) in the last 20-30 years. Young ponderosas rarely survive control burns and the result is invariably that oak and locust take over the forest floor. This is the worst idea yet from a National Forest mismanaged for 100 years. The control burn is the management tool of bureaucrats desperate for funding.

The primary study cited by the forest service as justification for their Nero-like plan to burn the forest and fiddle is actually a great work of science. It assesses forest structure, climate, burn frequency and to a certain extent, burn intensity. The study ends at the onset of the 20th century, due to human disturbance of the forest, and begins in the 19th century, because the climate in the 17th century created completely different conditions. It is not the fault of science that it has been perverted by a mad organization of out of control office workers in forest service uniforms.

This rather narrow study, focusing on a single century, within a forest with trees that lived for several centuries, has been the mother for the mantra, “control burns mimic reality”. The claim is that high frequency, low intensity fires visited the forest often, and that this must then be the new religion for the neo-Neros in uniform. Unfortunately, this grand conclusion is not at all supported by this, or any other study.

The truth is that a forest of old growth Ponderosa, several hundred years old, has a vastly different structure, and characteristics to modern forests that are the reeling remnant of insatiable greed and short sighted stupidity in forest management.

Of course, this kind of mania is not new to America. America has a long history of inventing fanciful fictions to support the fervor of pillage, from such gems as “rain follows the plow”, and the famous “Big rock candy mountain”.

To these we can add the fancy of burning the forest in order to save it.

Never mind that the supporting studies all covered fire during fire season, the Nero service will lie to the public about when fire season actually occurs to support their burn in the fall, winter, early spring, in fact, any time when moisture and wind/weather conditions will permit artificial blaze making. We used to throw people in jail for this kind of insanity, but when its the Nero service, well suddenly its all ok.

How does the Nero service answer the questions of destroying habitat, food, shelter, and forcing wildlife into conflict and deprivation on a maddening schedule?

They don’t. The Nero service will proudly proclaim that they need not concern themselves with such pedestrian matters.

The sad, inescapable reality is that humans cannot always undo what they have done. The same greedy eyes that felled the old growth forest for fun and profit provided no solutions for the result of their profiteering. Without the structure of an old growth forest, any study of fire is not transferable. Without the free action of centuries long interplays with flora and fauna, climate and moisture, there can be no replay of these same conditions.

The Nero service is continuing along with the tradition of ignorant arrogance, an attitude by which they seek to play with the lives and livelihood of countless species, and those that might yet emerge. No attempt will be made by them to correct their mistakes. Rather, they will continue to manufacture their fictions, and pound them into people’s heads, in an attempt to prove the theory that a lie repeated often enough becomes the truth.

Now we have come full circle. The Nero service seeks one last, great knockout blow for the Southern Jemez, a final spasm of suicidal glee, where the entire forest is to be converted to a grassland.

Ponderosas are weeds, sayeth the Nero service.

Fuel reduction reduces fire risk, they chant. Really? Better review those studies again. But wait, truth has never been a player in the mad fiddling of the Nero service, so why start now?

The best modern humans can hope for is for the forest they have annihilated to find its own will once again. This cannot be done by burning the forest. It cannot be done by logging the forest. It can only be done by working to understand the forest, not as an economic engine, or a storehouse for profit, but as a critical ecosystem interface where the forces of ecology and evolution interplay in their unique wild dance. Nothing in the so called restoration promises any of this, not even on a token level.

Brutal and stupid humans have a history of exhausting their resources, and then killing eachother, leaving, or simply dying off. Mohenjo-Daro, Harapa, Easter Island, the Mound builders, Chaco, the list goes on, the story has variations, but it is always the same. Still, the stupid and brutal are given the keys to resources they cannot cherish, in their drive for more, always more for themselves.

One would think, after several thousand years, that humanity might have learned something. The Nero service and their murderous plan prove that if we lead ourselves to believe we have learned anything, we are merely participating in the same self delusion as those who fervently declared that “rain follows the plow”.

This editorial is full of factual errors and misrepresentations of on the ground reality. First, the CFLRP project does not involve Santa Clara Pueblo or Bandelier National Monument lands. It only involves some Valles Caldera and Santa Fe National Forest lands. Second, the area in question was logged long ago and there have been no trees for Kay’s beloved logging families in this area since the 1950s. Past logging and overgrazing set up conditions for all of the forest fires she references and research shows that logging of large trees worsens fire behavior when natural or human caused fires occur. People on the right like to believe that commercial activities will help our forests. In fact the condition of our forests today and the big fires are largely caused by past logging and livestock grazing, not helped by these activities.

This comment is full of factual errors and misrepresentations of on the ground reality. First, there are no “beloved logging families,” there are only people who rely on wood to hear their homes. Second, the historically heavy logging in the area was encouraged by the USFS, not local communities, so skepticism of any solution that involves the USFS should be expected. Lastly, Kay’s is not a critique “from the right.” Remember, it was the USFS, in fact, that reorganized local subsistence economies in northern New Mexico into wage labor, market based economies in the 1940s, literally turning over the forests to commercial logging firms. When that scheme failed miserably, the USFS blamed locals for “overgrazing” and “clearcutting.”

David Correia